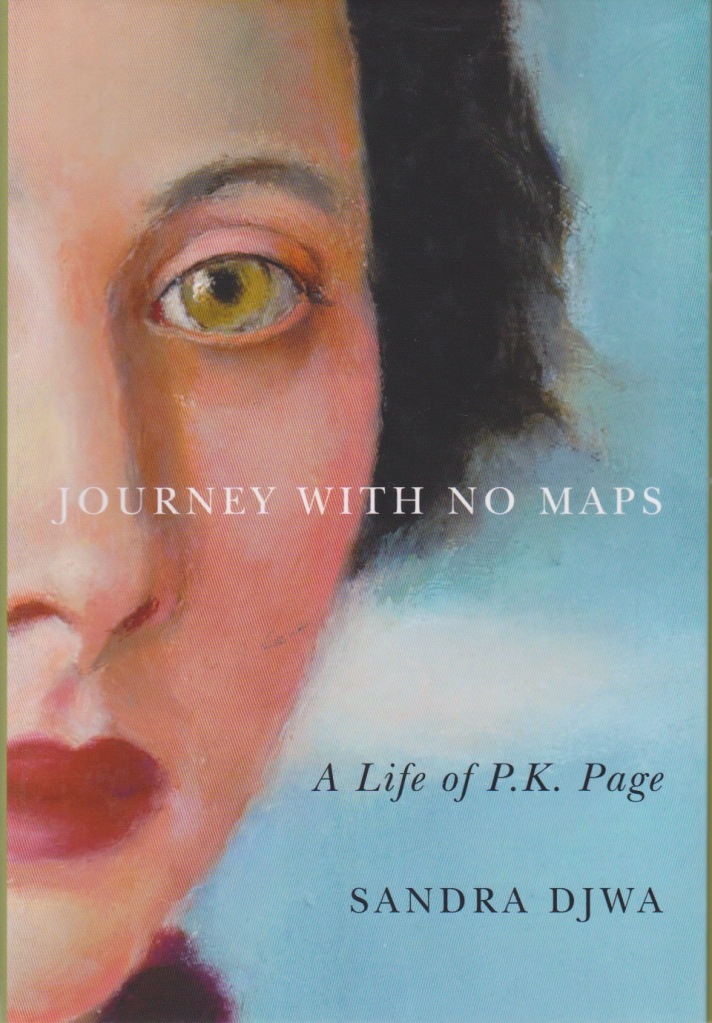

Review of Journey With No Maps: A Life of P.K. Page by Sandra Djwa (McGill Queen’s University Press) 2012: 418 pages.

Reviewed by Debra Martens

For the past few weeks I have been immersed in the life of poet and artist P.K. Page, as written by Sandra Djwa. Journey With No Maps is the kind of biography I like: chronological, lots of facts, nothing fictional. Djwa is a thorough biographer who clearly admires Page in both her life and work. First, though, I should tell you who I am writing about.

Patricia Kathleen Page’s long life (Nov. 1916-Jan. 2010) paralleled the rise of Canadian literature. She first published in the early journals Contemporary Verse and Preview, then went on to publish about 20 books of poetry and several books of prose. She won the Governor General’s Prize for Poetry in 1955 for The Metal and the Flower. Married to Arthur Irwin, she lived in Australia, Brazil and Mexico. When he retired from diplomacy, they settled in Victoria. While on posting, Page took up painting, showing and selling her work as P.K. Irwin. There you have it, the bare facts, which the biography fleshes out and connects up.

As for the biographer, Professor emerita of English (Simon Fraser) Sandra Djwa is also the author of a biography of poet F.R. Scott, The Politics of the Imagination. Not only that, she was asked by Page to be her biographer: you can’t get better credentials than that. My objection is that she does not tell us the whole truth about this author-biographer relationship in the Preface; instead, it is scattered throughout the book chronologically, from the opening line of Chapter 1 when she heard Page read a poem in Duthie’s Bookstore in Vancouver in the mid-1980s to several pages near the end of the book (pp. 264, 284-86, 297). Should the biographer appear in the biography if she knew her subject? That she scatters herself throughout does not feel right to me. She is consistent, however, in her chronological approach, as she also distributes Page’s interest in Sufism over many chapters, rather than in one section on Sufism (which some of us might like to skip).

Djwa starts with pioneer times, giving us the story behind the story. The first four chapters are information on Page’s parents and her early life, showing her early development as an artist, her exploration of modernism in London and theatre in Saint John. For me, however, the story really begins in October 1941 when Page took a room in the Epicurean Club at 1484 Sherbrooke Street in Montreal. And in that room, she wrote poetry, stories and plays.

Because she had published in Contemporary Verse, editor Patrick Anderson invited her to join the new poetry magazine Preview. She went along to the meeting at Frank and Marian Scott’s house, where she read aloud some of her poems, including “The Bones’ Voice,” and was immediately accepted into the group (see last week’s post). As she does throughout the book, Djwa uses this episode to demonstrate Page’s contribution to Canadian literature: “Pat clearly had an original voice. She went on to become a better poet than either Anderson or Scott…”(p. 76) On the publication of Page’s first book of poem, As Ten, As Twenty, Djwa writes, “A record of the war generation, it was very different from anything published previously in Canada in its unflinching combination of the realistic, the psychological, and the surreal. It includes a number of modern poems that rank among the best written in Canada…” (p. 112-3). Just so you know you are reading about an important poet.

When Page met Frank (F.R.) Scott, she was 26 and he was 42 and married. They became lovers in the fall of 1942. And who explains the attraction? Mavis Gallant. “I [Djwa] once asked Mavis Gallant, who had known both in Montreal in the forties, why the attraction?” Gallant said: “She was so beautiful all the men were in love with her, dark hair and creamy skin like a camellia. It was her big eyes. She had large eyes, grey, clear, thickly fringed dark lashes. Like her voice. Loved her poetry.” (p.89-90) Despite the evidence, I have trouble seeing them together, as Page’s work seems so much more modern than Scott’s to me.

In 1944 Page put an end to the affair by leaving Montreal. Yet as Djwa makes clear right up to Page’s final wishes, while the affair ended physically, Page never stopped loving Scott. Was that the reason she chose Djwa as her biographer, for the pleasure of having her lover’s biographer as her own?

From Montreal, Page went to Halifax, Vancouver, and then Ottawa, where she got a job writing scripts for the Film Commission (which became the NFB). Even in Ottawa, Page wanted to see Scott, hoping he would come from Montreal to visit. Finally Page and Marian forced Frank to choose between them; he chose his wife. And suddenly Page accepted a proposal of marriage from her boss, Arthur Irwin. Again, an older man, and in his case, with adult children. And it is here, in her relationship with Irwin, that I find the fleshing out gets skinny. Page seems to have married him for showing her a waterfall. Little is said about her relationship with his children or even him, until he is sick when they are in Victoria. Did she love him?

Soon after their marriage, Irwin was sent to Australia to serve as high commissioner from 1953-56. Despite “the rush of diplomatic life,” and that Page “no longer had the impetus of a close literary community,” Page was able to publish a book of poetry while there, and to start painting. In Brazil, she was unable to write, apart from journals, and devoted her portion of free time to drawing and painting, studying new techniques. She produced enough art for a show of her work in Toronto in 1960. She continued to study painting in Mexico, and to read books by Ouspensky, Gurdjieff, Jung, and notes by Idries Shah on Sufi subjects. After this posting, they moved to Victoria, B.C., where Page pursued Sufi studies and began to write again. She also discovered that she liked to give readings.

Did Page’s penchant for mysticism have anything to do with her inability to write in Brazil? Of learning another language, she wrote “Who am I , then, that language can so change me? What is personality, identity?” (p. 163)

In addition to her interviews with Page and Arthur Irwin, and other friends and colleagues, Djwa drew on Page’s unpublished journals and poems, and correspondence. In her acknowledgements she thanks over 200 people, including those that helped with the book during her ten years of working on it, and those who gave permission for their letters and interviews to be quoted. Thorough, then. In fact, even I, lover of facts, found there were perhaps too many, as were the names dropped.

Writers are not always honest in their journals, dashing words down in joy or haste, exaggerating for effect — a journal is sometimes a record and sometimes a treasure trove to be mined in the creative process. In fact, Djwa points this out, comparing edited and unedited passages of Page’s journal on a certain subject (pages 168, 174). Considering memory and the difficulty of interpreting a writer’s papers, considering that P.K. Page was interested in the story of her spiritual journey and not in dates, Djwa has done an amazing job of portraying the complexity of Page’s life and work. She has worked Page’s spiritual quest (“I have a destination but no maps.”) into a larger metaphor for the journey of a woman who made her way through the last century as exactly what she wanted to be.

But we were wrong and the map was true

and had we stood and looked about

from our height of land, we'd have had a view

which, since, we have had to learn by heart.

-from "The Map," by P.K.Page, in Hidden Room Vol. 2.

Related articles

- Dem Bones in last week’s Canadian Writers Abroad.

- Form for All: Paying Tribute, Page and the Glosa.

- Poems by P.K. Page at the Poetry Foundation.

- Djwa wins the Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-fiction in 2013.

- Page and husband Irwin honoured by Page Irwin Colloquium Room at Trent University (with photo of them).

Djwa’s title is lifted from Graham Greene’s account of his visit to Liberia in 1935, Journey without Maps.

LikeLike

I think Greene’s title might account for the wording of this title, in that it couldn’t be copied. But the concept comes from Page herself, who wrote in 1970, “I have a destination but no maps.” She didn’t mean real maps, as she was referring to her own development: “One’s route is one’s own. One’s journey unique.”

LikeLike